Read the original article on Dark Reading here.

Estonia and Monaco back up their citizens’ information to a data center in Luxembourg, while Singapore looks to India as its safe haven for data. But geopolitical challenges remain.

Source: Nikreates via Alamy Stock Photo

Worried about keeping data safe within their borders, a growing group of countries — typically, smaller nations — have hit upon a big idea: Redundantly hosting their citizens’ information in “data embassies” in another region but maintaining jurisdiction over it.

Just as an embassy is a nation’s territory on foreign soil, a data embassy holds data that is subject to the owner’s — not the host nation’s — laws. The goal of the data-embassy movement is to provide redundancy for critical data that might otherwise be lost in a cyberattack, natural disaster, or other catastrophe, explains Kelly Ahuja, CEO of Versa Networks, a network security firm.

“Data embassies are an interesting approach, designed to protect critical sovereign data from external cyber and physical threats,” he says, adding that such an arrangement also requires a secure way to manage the data. “Strong security controls, encryption, and data protection policies can be enforced on this network and the data that transits to protect against cyber threats, data breaches, and unauthorized access,” he says.

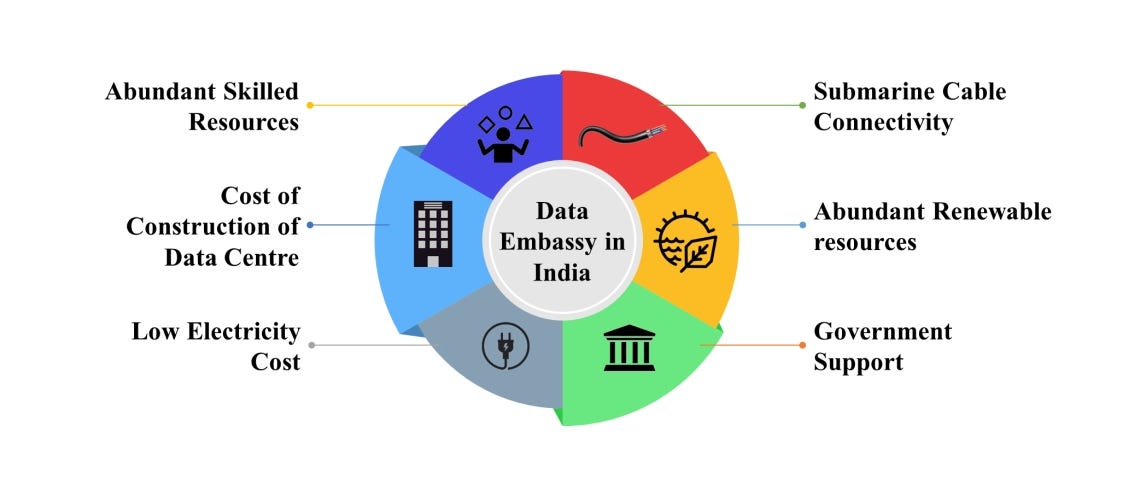

Typically, smaller countries especially look to external data havens as a hedge against disaster. In 2017, for instance, the Estonian government inked an agreement with Luxembourg to host the former Soviet republic’s data in a facility that “shall be inviolable and thus exempt from search, requisition, attachment, or execution.” And Monaco, a nation occupying about two square kilometers and worried about natural disasters, came to a similar agreement with Luxembourg in 2021. India has also reportedly opened negotiations with several countries, including Singapore and the United Arab Emirates, to host those nations’ data in its facilities located in special economic zones, such as the Gujarat International Finance Tec-City — often referred to as GIFT City.

The home country typically requires certain things from the hosting nation: sovereignty over its data, visibility into the facility’s operations, and a choice of the software used in the data center, Thiébaut Meyer, director in the office of the CISO for Google Cloud, wrote in a recent post on data embassies.

“The embassy framework has been slowly growing in appeal to entrepreneurial-minded countries,” he wrote. “To improve their resiliency, governments follow the same approach as organizations building a business continuity plan: For technical and organizational concerns, they identify their critical services, define a threat model, conduct a risk analysis, and enforce security measures and other controls to manage these risks.”

Complex Data Embassy Laws Offer Significant Challenges

For small countries, hosting data outside their borders seems an obvious solution, but it comes with challenges. For one, hosting citizens’ information in secure data centers abroad is a hefty investment. In addition, every agreement can face a variety of challenges because of regional geopolitics and changes in the domestic priorities of the host nation’s government, says Scott Jarnagin, CEO of Caddis Cloud Solutions, a data center advisory firm.

“Shifting political landscapes and leadership changes can impact agreements, potentially jeopardizing continued data access,” he says. “Additionally, evolving data sovereignty laws may introduce restrictions that conflict with prior arrangements, forcing costly relocations of active workloads.”

Because the legal protections to make data embassies work are complex and usually require long-standing economic and political relationships between the involved nations, the planning and negotiation process can be arduous, Jarnagin says.

In 2018, the Kingdom of Bahrain implemented legislation intended to facilitate the creation of data embassies, allowing home countries to store data in Bahrain but retain the governance of the data according to their domestic laws. The Cloud Law allows the government to designate a data center in the region as subject to external law, allowing foreign states to have jurisdiction there.

India will need to make investments to host a data embassy. Source: Communications Today (communicationstoday.co.in)

India will need to make investments to host a data embassy. Source: Communications Today (communicationstoday.co.in)

Yet the laws in those host countries have not faced a significant legal test, says Angel Nunez Mencias, chief technology officer at Phoenix Technologies AG, a sovereign cloud and blockchain company based in Switzerland.

“Unless the data center provider is on the campus of a [diplomatic] embassy, it is easier said than done to apply diplomatic protections to a commercial data center provider or hyperscaler,” he says. “International law is unclear with respect to legal status and protections afforded to these entities.” While existing diplomatic embassies might seem like a logical choice for hosting data, the reality is that many of those buildings, often historic locations, are not set up in terms of power or connectivity for modern data center activities.

“Jurisdiction Shopping”: Is One Data Center Enough?

With geopolitical alliances currently in flux, “jurisdiction shopping” is a growing trend. And committing to a single data center in one country may not be enough, Mencias says. Instead, a network of data embassies may be a more resilient solution, both geopolitically and technologically.

“Jurisdictions offering robust legal frameworks provide greater predictability and protection for data and AI-related activities, influencing the choice of location,” he says. “A network of data embassies around the world participating as a consortium [could allow countries to] shop amongst these providers and be assured that [they] would provide necessary resiliency in the face of an attack.”

Finally, government agencies also have to worry about securely transferring data to and from the data embassies, which requires strict security controls, strong encryption, and resilient data protection both in the data center and on the networks transporting the data, Versa’s Ahuja says. This type of approach — a sovereign secure access service edge (SASE) — gives the data owner control over the infrastructure as well.

“If you are transporting sovereign data out to a third-party data embassy over an insecure network, [our] approach [is] to secure networking where governments can build and manage their own dedicated SASE infrastructure, rather than relying on ‘shared’ SASE networks hosted in these hyperscaler clouds,” he says.

Caddis has taken the remote data center concept even further — literally. The company has inked a deal with startup Lonestar Lunar to host data away from Earth, and earthly jurisdictions, and instead aim for the moon.

“Storing data on the moon provides countries and companies with a whole new level of data security that is based on the moon via satellite,” says Caddis’ Jarnagin, adding: “As climate-related disasters become more frequent and severe, space-based data storage offers a disaster recovery option that ensures data is available even in extreme events.”